Search results

People also ask

Where did chess come from?

Who invented chess?

When did chess become popular in India?

How has chess changed over time?

The history of chess can be traced back nearly 1,500 years to its earliest known predecessor, called chaturanga, in India; its prehistory is the subject of speculation. From India it spread to Persia, where it was modified in terms of shapes and rules and developed into Shatranj.

- Overview

- Ancient precursors and related games

- Introduction to Europe

- Standardization of rules

- Set design

- The world championship and FIDE

- Women in chess

The origin of chess remains a matter of controversy. There is no credible evidence that chess existed in a form approaching the modern game before the 6th century ce. Game pieces found in Russia, China, India, Central Asia, Pakistan, and elsewhere that have been determined to be older than that are now regarded as coming from earlier distantly related board games, often involving dice and sometimes using playing boards of 100 or more squares.

One of those earlier games was a war game called chaturanga, a Sanskrit name for a battle formation mentioned in the Indian epic Mahabharata. Chaturanga was flourishing in northwestern India by the 7th century and is regarded as the earliest precursor of modern chess because it had two key features found in all later chess variants—different pieces had different powers (unlike checkers and go), and victory was based on one piece, the king of modern chess.

How chaturanga evolved is unclear. Some historians say chaturanga, perhaps played with dice on a 64-square board, gradually transformed into shatranj (or chatrang), a two-player game popular in northern India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and southern parts of Central Asia after 600 ce. Shatranj resembled chaturanga but added a new piece, a firzān (counselor), which had nothing to do with any troop formation. A game of shatranj could be won either by eliminating all an opponent’s pieces (baring the king) or by ensuring the capture of the king. The initial positions of the pawns and knights have not changed, but there were considerable regional and temporal variations for the other pieces.

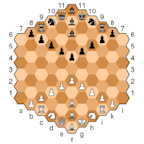

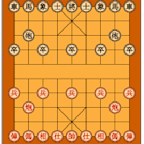

The game spread to the east, north, and west, taking on sharply different characteristics. In the East, carried by Buddhist pilgrims, Silk Road traders, and others, it was transformed into a game with inscribed disks that were often placed on the intersection of the lines of the board rather than within the squares. About 750 ce chess reached China, and by the 11th century it had come to Japan and Korea. Chinese chess, the most popular version of the Eastern game, has 9 files and 10 ranks as well as a boundary—the river, between the 5th and 6th ranks—that limits access to the enemy camp and makes the game slower than its Western cousin.

The origin of chess remains a matter of controversy. There is no credible evidence that chess existed in a form approaching the modern game before the 6th century ce. Game pieces found in Russia, China, India, Central Asia, Pakistan, and elsewhere that have been determined to be older than that are now regarded as coming from earlier distantly related board games, often involving dice and sometimes using playing boards of 100 or more squares.

One of those earlier games was a war game called chaturanga, a Sanskrit name for a battle formation mentioned in the Indian epic Mahabharata. Chaturanga was flourishing in northwestern India by the 7th century and is regarded as the earliest precursor of modern chess because it had two key features found in all later chess variants—different pieces had different powers (unlike checkers and go), and victory was based on one piece, the king of modern chess.

How chaturanga evolved is unclear. Some historians say chaturanga, perhaps played with dice on a 64-square board, gradually transformed into shatranj (or chatrang), a two-player game popular in northern India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and southern parts of Central Asia after 600 ce. Shatranj resembled chaturanga but added a new piece, a firzān (counselor), which had nothing to do with any troop formation. A game of shatranj could be won either by eliminating all an opponent’s pieces (baring the king) or by ensuring the capture of the king. The initial positions of the pawns and knights have not changed, but there were considerable regional and temporal variations for the other pieces.

The game spread to the east, north, and west, taking on sharply different characteristics. In the East, carried by Buddhist pilgrims, Silk Road traders, and others, it was transformed into a game with inscribed disks that were often placed on the intersection of the lines of the board rather than within the squares. About 750 ce chess reached China, and by the 11th century it had come to Japan and Korea. Chinese chess, the most popular version of the Eastern game, has 9 files and 10 ranks as well as a boundary—the river, between the 5th and 6th ranks—that limits access to the enemy camp and makes the game slower than its Western cousin.

A form of chaturanga or shatranj made its way to Europe by way of Persia, the Byzantine Empire, and, perhaps most important of all, the expanding Arabian empire. The oldest recorded game, found in a 10th-century manuscript, was played between a Baghdad historian, believed to be a favourite of three successive caliphs, and a pupil.

Muslims brought chess to North Africa, Sicily, and Spain by the 10th century. Eastern Slavs spread it to Kievan Rus about the same time. The Vikings carried the game as far as Iceland and England and are believed responsible for the most famous collection of chessmen, 78 walrus-ivory pieces of various sets that were found on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides in 1831 and date from the 11th or 12th century. See Figure 2.

The modern rules and appearance of pieces evolved slowly, with widespread regional variation. By 1300, for example, the pawn had acquired the ability to move two squares on its first turn, rather than only one at a time as it did in shatranj. But this rule did not win general acceptance throughout Europe for more than 300 years.

Chess made its greatest progress after two crucial rule changes that became popular after 1475. Until then the counselor was limited to moving one square diagonally at a time. And, because a pawn that reached the eighth rank could become only a counselor, pawn promotion was a relatively minor factor in the course of a game. But under the new rules the counselor underwent a sex change and gained vastly increased mobility to become the most powerful piece on the board—the modern queen. This and the increased value of pawn promotion added a dynamic new element to chess. Also, the chaturanga piece called the elephant, which had been limited to a two-square diagonal jump in shatranj, became the bishop, more than doubling its range.

Until these changes occurred, checkmate was relatively rare, and more often a game was decided by baring the king. With the new queen and bishop powers, the trench warfare of medieval chess was replaced by a game in which checkmate could be delivered in as few as two moves.

The last two major changes in the rules—castling and the en passant capture—took longer to win acceptance. Both rules were known in the 15th century but had limited usage until the 18th century. Minor variations in other rules continued until the late 19th century; for example, it was not acceptable in many parts of Europe as late as the mid-19th century to promote a pawn to a queen if a player still had the original queen.

The appearance of the pieces has alternated between simple and ornate since chaturanga times. The simple design of pieces before 600 ce gradually led to figurative sets depicting animals, warriors, and noblemen. But Muslim sets of the 9th–12th centuries were often nonrepresentational and made of simple clay or carved stone following the Islamic prohibition of images of living creatures. The return to simpler, symbolic shatranj pieces is believed to have spurred the game’s popularity by making sets easier to make and by redirecting the players’ attention from the intricate pieces to the game itself.

Stylized sets, often adorned with precious and semi-precious stones, returned to fashion as the game spread to Europe and Russia. Playing boards, which had monochromatic squares in the Muslim world, began to have alternating black and white, or red and white, squares by 1000 ce and were often made of fine wood or marble. Peter I (the Great) of Russia had special campaign boards made of soft leather that he carried during military efforts.

The king became the largest piece and acquired a crown and sometimes an elaborate throne and mace. The knight’s close identification with the horse dates back to chaturanga. The pawn, as the lowest in power and social standing, has traditionally been the smallest and least representational of the pieces. The queen grew in size after 1475, when its powers expanded, and changed from a male counselor to the king’s female consort. The bishop was known by different names—“fool” in French and “elephant” in Russian, for example—and was not universally recognized by a distinctive mitre until the 19th century. Depiction of the rook also varied considerably. In Russia it was usually represented as a sailing ship until the 20th century. Elsewhere it was a warrior in a chariot or a castle turret.

The standard for modern sets was established about 1835 with a simple design by an Englishman, Nathaniel Cook. After it was patented in 1849, the design was endorsed by Howard Staunton, then the world’s best player; because of Staunton’s extensive promotion, it subsequently became known as the Staunton pattern. Only sets based on the Staunton design are allowed in international competition today. See Figure 3.

The popularity of chess has for the past two centuries been closely tied to competition, usually in the form of two-player matches, for the title of world champion. The title was an unofficial one until 1886, but widespread spectator interest in the game began more than 50 years earlier. The first major international event was a series of six matches held in 1834 between the leading French and British players, Louis-Charles de la Bourdonnais of Paris and Alexander McDonnell of London, which ended with Bourdonnais’s victory. For the first time, a major chess event was reported extensively in newspapers and analyzed in books. Following Bourdonnais’s death in 1840, he was succeeded by Staunton after another match that gained international attention, Staunton’s defeat of Pierre-Charles Fournier de Saint-Amant of France in 1843. This match also helped introduce the idea of stakes competition, since Staunton won the £100 put up by supporters of the two players.

Staunton used his position as unofficial world champion to popularize the Staunton-pattern set, to promote a uniform set of rules, and to organize the first international tournament, held in London in 1851. Karl Ernst Adolf Anderssen, a German schoolteacher, was inspired by the Bourdonnais-McDonnell match to turn from problem composing to tournament competition, and he won the London tournament and with it recognition as unofficial champion. The London tournament, in turn, inspired American players to organize the first national championship, the First American Chess Congress, in New York City in 1857, which set off the first chess craze in the Western Hemisphere. The winner, Paul Morphy of New Orleans, was recognized as unofficial world champion after defeating Anderssen in 1858.

The world championship became more formalized after Morphy retired and Anderssen was defeated by Wilhelm Steinitz of Prague in a match in 1866. Steinitz was the first to claim the authority to determine how a title match should be held. He set down a series of rules and financial conditions under which he would defend his status as the world’s foremost player, and in 1886 he agreed to play Johann Zukertort of Austria in the first match specifically designated as being for the world championship. Steinitz reserved the right to determine whose challenge he would accept and when and how often he would defend his title.

Steinitz’s successor, Emanuel Lasker of Germany, proved a more demanding champion than Steinitz in arranging matches. He took long periods, from 1897 to 1907 and later from 1910 to 1921, without defending his title. After the leading national chess federations, the British and German, failed to arrange a match between Lasker and any of his leading challengers on the eve of World War I, the momentum for an independent international authority began to grow.

The controversy over the championship was eased when José Raúl Capablanca of Cuba defeated Lasker in 1921 and won the agreement, at a tournament in London in 1922, of the world’s other leading players to a written set of rules for championship challenges. Under those rules, any player who met certain financial conditions (in particular, guaranteeing a $10,000 stake) could challenge the World Champion. While the top players were trying to adhere to the London Rules, representatives of 15 countries met in Paris in 1924 to organize the first permanent international chess federation, known as FIDE, its French acronym for Fédération Internationale des Échecs.

The London Rules worked smoothly in 1927 when Capablanca was dethroned by Alexander Alekhine, the first Russian-born champion, but then proved to be a financial obstacle in Capablanca’s bid for a rematch. FIDE’s attempts to intervene failed. Alekhine was widely criticized for manipulating the rules, and when he died in 1946 FIDE assumed the authority to organize world championship matches.

Separation of the sexes in chess dates from about 1500 with the introduction of the queen. Chess became a much faster, more exciting game and, thus, came to be perceived as a more masculine pursuit. Women were often barred from the coffeehouses and taverns where chess clubs developed in the 19th century. However, women players achieved distinction separately from men by the middle of the century. The first chess clubs specifically for women were organized in the Netherlands in 1847. The first chess book written by a woman, The ABC of Chess, by “A Lady” (H.I. Cooke), appeared in England in 1860 and went into 10 editions. The first women’s tournament was sponsored in 1884 by the Sussex Chess Association.

Women also gained distinction in postal and problem chess during this period. An American woman, Ellen Gilbert, defeated a strong English amateur, George Gossip, twice in an international correspondence match in 1879—announcing checkmate in 21 moves in one game and in 35 moves in the other. Edith Winter-Wood composed more than 2,000 problems, 700 of which appeared in a book published in 1902.

The first woman player to gain attention in over-the-board competition with men was Vera Menchik (1906–44) of Great Britain. She won the first Women’s World Championship, a tournament organized by FIDE in 1927, and the next six women’s championship tournaments, in 1930–39. Her good results against men in British events led to invitations to some of the strongest pre-World War II tournaments, including Carlsbad 1929 (tournaments are identified by venue and year) and Moscow 1935. Among the strong male masters who lost to her were the world champion Max Euwe, Samuel Reshevsky, Sultan Khan, Jacques Mieses, Edgar Colle, and Frederick Yates. She was also one of the first women chess professionals.

Women’s chess received a major boost when the Soviet Union endorsed separate women’s tournaments as part of a general encouragement of the game. The 1924 women’s championship of Leningrad was the first women’s tournament sponsored by any government. Massive events, larger than anything open to either sex in the West, followed; nearly 5,000 women took part in the preliminary sections of the 1936 Soviet women’s championship, for example.

Improvements in playing strength ensued and led to Soviet domination of women’s chess for more than 30 years. After Menchik’s death, FIDE held a 16-player tournament in Moscow during the winter of 1949–50 to fill the vacancy. Soviet women took the top four places.

The Women’s World Championship has been decided by matches or elimination match tournaments organized by FIDE since 1953. After Menchik’s death the next three champions were Ludmilla Rudenko of Ukraine and Elizaveta Bykova and Olga Rubtsova of Russia. But, with the victory of Nona Gaprindashvili in 1962, an era of supremacy by Georgian players began. Gaprindashvili held the title for 16 years and became the first woman to earn the title of International Grandmaster. (FIDE established separate titles of International Woman Master in 1950 and International Woman Grandmaster in 1977.) Gaprindashvili was succeeded by another Georgian, Maya Chiburdanidze, in 1978. Georgians also won the right to challenge the champions in 1975, 1981, and 1988.

Oct 15, 2021 · Chess is an ancient game, approximately 1500 years old. This game originated in northern India in the 6th century AD as Chaturanga and spread to Persia. If you want to get to know about the complete history of chess, then read this timeline carefully. Earliest History of Chess

The recorded history of chess goes back at least to the emergence of a similar game, chaturanga, in seventh-century India. The rules of chess as they are known today emerged in Europe at the end of the 15th century, with standardization and universal acceptance by the end of the 19th century.

Chess first appeared in India about the 6th century CE. By the 10th century it had spread from Asia to the Middle East and Europe. Some regard the game chaturanga to be the precursor of modern chess because of the different piece abilities and the win condition being the capture of a singular piece (king).

Jan 28, 2009 · Learn how chess originated from India and evolved over time with global trade and tournaments. Find out the 10 most important moments of chess history and the terms and players that shaped the game.