Search results

People also ask

Who is Clarence Thomas?

Why did Clarence Thomas leave the Supreme Court?

Who is Clarence Thomas wife Ginni Thomas?

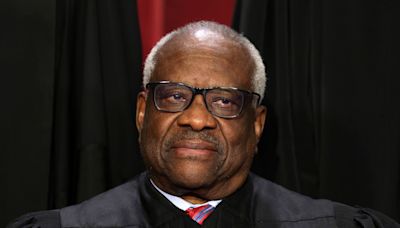

Clarence Thomas (born June 23, 1948) is an American lawyer and jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was nominated by President George H. W. Bush to succeed Thurgood Marshall and has served since 1991.

4 days ago · CNN —. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas did not attend oral arguments Monday and provided no explanation for his absence. Chief Justice John Roberts announced that Thomas would not take ...

4 days ago · Justice Clarence Thomas, 75, is the Supreme Court's oldest member and the most senior associate justice. He joined the court in 1991. All 12 jurors for Donald Trump's hush money trial in NY have ...

3 days ago · WASHINGTON (Reuters) - U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas returned to the bench on Tuesday, a day after he missed arguments in two cases with no explanation offered by the court. Thomas ...

- Overview

- Early life and education

- Department of Education and Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

- Federal judgeship and nomination to the Supreme Court

- Supreme Court opinions and jurisprudence

- Judicial ethics controversies

Clarence Thomas (born June 23, 1948, Pin Point, near Savannah, Georgia, U.S.) associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1991, the second African American to serve on the Court. Appointed to replace Thurgood Marshall (1908–93), the Court’s first African American member, Thomas gave the Court a decisive conservative cast.

Thomas was the second of three children born to Leola (née Anderson, subsequently Williams) and M.C. Thomas. Clarence Thomas’s parents wed as teenagers at the insistence of Leola’s father, Myers Anderson, after Leola became pregnant with Thomas’s elder sister, Emma. The couple divorced in 1950, having separated in 1949. M.C. Thomas was not involved in his children’s lives.

Britannica Quiz

All-American History Quiz

For a time, Clarence Thomas, his mother, and his siblings lived in Pin Point, near Savannah, Georgia, in a house owned by Annie, their mother’s aunt. After the house was destroyed in a fire in 1954, his mother moved with Thomas and his brother to Savannah, while his sister remained with Annie. In the summer of 1955 Thomas and his younger brother, Myers, were sent to live with their maternal grandfather and his wife, Christine Anderson. Their grandfather, within Savannah’s segregated Black community a comparatively wealthy entrepreneur, demanded that Thomas and his brother work hard and excel in school. Thomas’s autobiography, titled My Grandfather’s Son: A Memoir (2007), attributes his own discipline and work ethic to the lessons imparted to him by Anderson.

For most of his childhood, Thomas attended all-Black Roman Catholic schools in Savannah. In his memoir Thomas recalled that other Black students were prejudiced against him for his dark skin and Geechee (or Gullah) heritage. He offered fonder memories of his primary-school teachers—white nuns who demanded excellence in the classroom and defended their students’ dignity on class field trips around Savannah.

In 1964, after two years at St. Pius X High School, Thomas transferred to St. John Vianney Minor Seminary, seeking to become a Roman Catholic priest. Thomas was one of two Black students at the seminary, which had never enrolled a Black student before Thomas’s arrival (the other Black student left after one year). Thomas was regularly the target of racist insults from his white classmates and teachers but graduated in 1967 with top grades.

Following his graduation from Yale in 1974, Thomas went to work in the office of the Missouri attorney general, Republican John (“Jack”) Danforth, in Jefferson City. During this time Thomas began to express more consistently conservative views. He opposed policies such as affirmative action and school integration via busing because, he argued, they harmed the interests and well-being of Black people.

Following Danforth’s election to the U.S. Senate in 1977, Thomas took a job in the legal department of Monsanto, a major chemical company based in the St. Louis, Missouri, metropolitan area. In 1979 he moved to Washington, D.C., to work as a legislative assistant to Danforth.

Thomas’s developing political views were influenced by prominent Black conservatives including J.A. (“Jay”) Parker, considered the founder of the Black conservative movement, and the economists Thomas Sowell and Walter E. Williams. In December 1980 Thomas attended a “Black Alternatives Conference” in San Francisco organized by Sowell, Williams, and the economist Milton Friedman. There Thomas caught the attention of a Washington Post journalist, Juan Williams, who wrote an article about him. The resulting national exposure stirred interest in Thomas within the new Republican administration of Pres. Ronald Reagan. But the article also attracted criticism from liberal Black leaders, in part for Thomas’s opposition to liberal economic programs designed to benefit Black people, who for centuries had been denied the same economic opportunities enjoyed by whites. In his article, Williams quoted Thomas as claiming that his own sister was “dependent” on welfare and had “no motivation for doing better or getting out of that situation”—comments that were characterized by other Black leaders as insensitive and unfair.

In 1981 Thomas was appointed assistant secretary for civil rights at the U.S. Department of Education. That same year Thomas and his wife separated. They divorced in 1984, agreeing that Thomas would take custody of their son, Jamal.

At the Department of Education Thomas opposed efforts to push Southern states to increase multiracial access to historically Black or white state universities, —a policy goal that Thomas viewed as weakening the ability of Black institutions to serve the distinct needs of Black students and communities. He also opposed the Reagan administration’s efforts to defend the tax-exempt status of Bob Jones University, a private religious and educational institution in Greenville, South Carolina, despite that school’s policy of banning interracial dating and marriage between students and denying admission to students engaged in interracial marriage or known to advocate interracial dating or marriage. (In 1983, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Bob Jones University did not qualify for tax-exempt status because its admissions policy was racially discriminatory; see Bob Jones University v. United States.)

In 1982 Reagan nominated Thomas to the chairmanship of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). Confirmed by the Senate in May of that year, Thomas served two four-year terms with the agency. When he arrived, the EEOC’s finances were in disarray and the agency faced a significant backlog of unresolved complaints. Under Thomas’s leadership, the EEOC became better organized.

In October 1989, Republican Pres. George H.W. Bush nominated Thomas to a seat on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, which is widely regarded as the second most powerful court in the United States (after the U.S. Supreme Court) because of the frequency with which it decides cases implicating the interpretation of federal law. Judgeships on the court are perceived as a professional springboard to the Supreme Court. (In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, U.S. Supreme Court justices who served on District of Columbia Circuit immediately before their elevation to the Supreme Court included Thomas, Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., Antonin Scalia, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Brett Kavanaugh, and Ketanji Brown Jackson.) Thomas was confirmed by the Senate in March 1990.

Thomas’s name regularly appeared on shortlists of potential Supreme Court nominees. In 1991 the ailing Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall announced that he would retire at the end of the Court’s 1990–91 term. Marshall, the Court’s first Black member, was known for his liberal jurisprudence, particularly with respect to constitutional issues implicating race. The fact that Bush, a Republican, would choose Marshall’s replacement meant that the ideological makeup of the Supreme Court was very likely to change.

On July 1, 1991, Bush announced his nomination of Thomas to the Supreme Court. Given the likely political consequences of replacing a liberal such as Marshall with a conservative such as Thomas, liberals and Democrats subjected Thomas to significant scrutiny. Abortion rights activists were especially critical of Thomas, claiming that he would vote to undermine or altogether eliminate the right to abortion protected by the Supreme Court’s 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade. (Thomas did indeed vote to overturn Roe as well as Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey [1992], joining the Court’s conservative majority in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization [2022]. See below Supreme Court opinions and jurisprudence.)

The Democratic Party controlled the Senate by a 57–43 majority, which meant that Thomas’s confirmation would require the support of at least seven Democratic senators. At hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee, chaired by then Sen. Joe Biden, a Democrat, Thomas evaded Democratic senators’ questions about how he would rule in cases related to abortion, asserting that he had taken no position on Roe v. Wade and that he had never discussed the landmark ruling with colleagues, law school classmates, or even his wife. The committee, evenly divided between Thomas’s critics and supporters, reported his nomination to the full Senate without a recommendation.

As a Supreme Court justice, Thomas’s voting pattern was overwhelmingly conservative, and his conservative rulings contributed to a perception that he was a Republican-friendly justice. As a result, he became a polarizing figure in American politics, generally praised by Republicans and criticized by Democrats.

Thomas consistently voted with his fellow conservatives on major cases with political implications that cleaved the Court along partisan lines. Most famously, in Bush v. Gore (2000), Thomas joined four other conservative justices in a ruling that halted a vote recount in Florida and effectively decided the 2000 presidential election in favour of George W. Bush. Thomas joined conservative blocs in other prominent 5–4 decisions implicating elections and voting, including Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010), which struck down federal legislation limiting corporate spending on behalf of political candidates; Shelby County v. Holder (2013), which eliminated the Voting Rights Act’s requirement that certain states obtain federal “preclearance” for any changes to their electoral laws; and Rucho v. Common Cause (2019), which declared that partisan gerrymandering by state legislatures is a “political question” not subject to federal judicial review.

Thomas also dissented in two Supreme Court cases that upheld key provisions of the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), considered the major legislative achievement of Democratic Pres. Barack Obama. In National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (2012), Thomas argued that, in adopting a provision of the PPACA known as the individual mandate (a requirement that most Americans carry health insurance by 2014 or pay a penalty), Congress had exceeded its powers under the U.S. Constitution’s commerce clause (Article I, Section 8), which authorizes Congress “to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with Indian Tribes.” And in King v. Burwell (2015) he joined a dissent by Justice Scalia, who argued for a narrower reading of the PPACA that would likely have led to the loss of health-insurance subsidies for millions of people.

Thomas was a practitioner and advocate of the philosophy of constitutional interpretation known as originalism. Originalism purports to give the U.S. Constitution’s text the meaning it was understood by the public to have at the time of its adoption. Originalists argue that their approach is the only legitimate method of interpreting the Constitution—that its meaning is fixed and unchangeable over time and that justices are obliged to respect this meaning even if they do not personally agree with the rulings that it may entail. Critics of originalism argue that much of the Constitution—particularly those provisions that have led to contentious legal cases—never had a single clear meaning and that, in practice, purported attempts to discern such a meaning enable judges to reach any decision they desire.

Early in his tenure on the Court, Thomas was accused of simply following the lead of Justice Scalia, another ardent originalist, whose decisions Thomas frequently joined. Both Scalia and Thomas adamantly rejected this notion. Legal scholars who analyzed their writings noted that Thomas generally demonstrated a stronger commitment than Scalia to originalist principles and a greater willingness to use originalism to overturn judicial precedents.

Relatively few of Thomas’s majority opinions were written in landmark constitutional cases. He often wrote separate dissenting or concurring opinions that represented a conservative extreme among the sitting justices and suggested an unwillingness to compromise in his reasoning in order to attract other justices to his views. At the Court’s oral arguments, Thomas rarely asked questions. Critics suggested that this showed disengagement or closed-mindedness, but Thomas disputed those claims, noting that he was always well prepared for cases and that oral arguments have a public-facing performative element (for attorneys and justices) that he did not see a reason to engage in.

Thomas’s critics cited other episodes from his professional and personal life as evidence of an alleged bias in favour of Republican and conservative causes. Many such criticisms centred on Thomas’s second wife, Ginni Thomas, who has maintained a prominent career as a Republican activist throughout his time on the Court. In the aftermath of the 2020 presidential election, in which Republican Pres. Donald Trump was defeated by the Democratic candidate, Joe Biden, she was involved in efforts to overturn the results of the election, communicating with the Trump White House and lobbying legislators in the closely contested states of Arizona and Wisconsin.

Thomas’s work as a justice was implicated in his wife’s activism in the 2020 election. He was the only justice to oppose the Supreme Court’s refusal in January 2022 to block (on the grounds of executive privilege) the production of records from the Trump White House that had been requested by a House select committee investigating the January 6 U.S. Capitol attack and Trump’s possible role in the violence. The subsequently released records included communications from Ginni Thomas encouraging Trump’s campaign to fight to overturn the election, which prompted criticism of Thomas for not having recused himself from the Court’s decision.

4 days ago · By Lawrence Hurley. WASHINGTON — Conservative Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas was not present at the court for oral arguments Monday, with the court giving no reason for his absence. Chief ...

4 days ago · Justice Clarence Thomas poses during a group photo of the justices at the Supreme Court in Washington, U.S., April 23, 2021. Erin Schaff/Pool via REUTERS/File Photo Purchase Licensing Rights